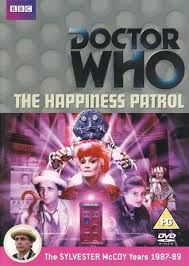

Aired 2 – 16 November 1988

‘The Happiness Patrol’ has enjoyed a surprisingly strong legacy since its airing, able to overcome the always-present dwindling budget and the often-ropey special effects to deliver a powerful allegory of England in the late 1980s. It’s no secret that new script editor Andrew Cartmel intended to more firmly ground his Doctor Who era by not shying away from political and social issues of the time, but ‘The Happiness Patrol’ calls into question Margaret Thatcher and her policies quite directly, ensuring it remains an enduring symbol of a time not so far past.

Sheila Hancock does sublime work as Helen A, and it’s impossible not to see the parallels between Thatcher and her from the very start. Operating within an overtly-fascist regime, Helen A is simultaneously grating and enduring as she casually modifies the Bureau’s protocols to suit her own needs and maintain control over a clearly-oppressed underclass. Of course, as the workers protest for better conditions, Helen A is quick to point out that those same workers have nobody to blame for their situation but themselves, even as she strives to further subdue them while breaking up any formal groups or representation. Indeed, Helen A’s comments that the world is made worse by the workers’ complaints and that the workers simply need to pick themselves up and better themselves very closely resemble Thatcher’s comments about the working class she oversaw, and it’s quite telling that Helen A also accepts no personal blame once her regime has fallen.

Fascinatingly, though, ‘The Happiness Patrol’ doesn’t simply tell a superficial story about forced happiness with one character mirroring a real-life figure. It bravely blazes into much deeper territory as well, by suggesting this futuristic colony is one in which any degree of individualism is a crime. If one doesn’t fit in with the ideals of the whole or dares to suggest a novel opinion, he or she becomes a threat to society and needs to be handled quickly before destroying the strict normality of the culture. While this particular sentiment unfortunately still rears its head from time to time for any number of reasons, it resonates particularly strongly with the preconceptions and misinformation that plagued both the gay community and AIDS victims in general at the time of broadcast, evidenced by similar sentiments voiced by Thatcher and others in important public positions. It is surely no coincidence that legislation to stop the so-called promotion of homosexuality was passed around the time of this serial’s production, and the duality of the forced happiness both in terms of supposedly improving society as well as for different subsets to persist and carry on within an unhappy culture in general works incredibly well.

This serial also continues the trend of having the Seventh Doctor become a much more purposeful force, here appearing on Terra Alpha to clear up the mystery surrounding reports of a great evil. Once he discovers Helen A’s regime and its attempts to control society both physically and emotionally, he has no qualms about getting involved and wreaking havoc with the perceived norms of the culture, especially once he has disproven Helen A’s own mantra and proven that even she must experience despair. As the story calls into question people who refuse to speak up for their rights, ‘The Happiness Patrol’ is unquestionably Doctor Who at its most political and proof that the franchise still had plenty of viability left in it despite the shrinking audience and corporate support.

Leave a Reply