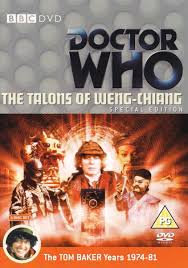

Aired 26 February – 2 April 1977

‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’ routinely hovers at or around the top of lists of favourite episodes, and it’s unquestionably a highlight of the overall theme and tone of the Tom Baker years with Philip Hinchcliffe as producer. Utilizing several trusted tropes of the romantic and dangerous Victorian era to bring the past to life exceedingly well, ‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’ is drenched in atmosphere as the fascinating mystery behind a stage magician and ventriloquist and his prop doll slowly unfolds.

That said, there are two points of contention with the story which carry different levels of weight for different people. The first is the overreliance on the giant rat special effects which are sadly lacking in execution. While dodgy effects and Doctor Who typically go hand in hand, the gritty realism of the story as a whole makes them all the more noticeable here, and the fact that two cliffhangers hinge on its appearance draws even more attention the failure of realism to meet the ambition of imagination. Wisely, though, the story does not shy away from some of the less favourable aspects of Victorian London, including racism and prejudice. While the ability of all of the Chinese to know some form of martial arts and the mysticism of Li H’Sen Chang can be forgiven as an homage to other tales of the time and do certainly enhance the tale being told, the unwillingness or inability to cast a Chinese actor as the Chang does stick out as a strange decision that again undermines the otherwise intense atmosphere and realism. These are not fatal flaws, and they certainly can be overlooked within the context of the time, but they do stick out nonetheless in an otherwise seamless tale.

Indeed, there is an air of theatricality throughout the entire production that runs much deeper than simply having the theatre setting play a major role in events, and this helps to sell the reliance on stereotypes of the era immensely. Even the superstitions and quasi-religion built around Weng-Chiang work to great effect without ever dominating events, and the suggestion that Chang’s belief in Weng-Chiang as a god is evidence of a mental breakdown is quite fascinating within the context of the story. Of course, the superb double act that results from pairing theatre owner Henry Gordon Jago with pathologist Professor Litefoot further exemplifies the theatricality and the duo instantly steal the show whenever they are together; Jago’s thought of turning the villain’s den into a tourist spot is suitably surreal and realistic at the same time.

‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’ revels in the stereotypes of Victorian London and popular connotations of Sherlock Holmes tales, utilizing fog, hansom cabs, and the prospect of something secret lurking in plain sight to great effect. Indeed, the spectre of Jack the Ripper looms large over this story, both explicity and subtly. Though it’s never quite stated why Greel chooses only to use women as victims to extend his own life while captured men are simply killed and tossed aside, it is quite clear that prostitutes are the intended victim, a bold storytelling choice for Doctor Who in any time period and again adding to the pulpy realism of the setting. While the Peking Homunculus is also a fascinatingly macabre concept rooted in a history of horror given a strong science fiction basis, the more intriguing notion is that Greel is a fugitive from the future and that ‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’ is a continuation of an untelevised story that more fully deals with the Zigma experiment and the title of The Butcher of Brisbane.

‘The Talons of Weng-Chiang’ is a testament to Philip Hinchcliffe’s vision for the show, perfectly blending together incredible atmosphere, horror, and fantasy perfectly. Though it’s perhaps not the showcase for Leela that her debut story was, she still proves that she is more formidable than the typical companion and will always be a fascinating presence whether in her native environment or in Earth’s more recent past. While there are some issues that will be more noticeable to some in this current time than to others, the overall result is an absolute classic that is all the more impressive given how hurriedly it was allegedly written.

Leave a Reply